NOTE: This is part two of the Whipple Creek Park project. Part one provides an overview of the project.

“It’s an Emergency, we need help. I have no idea where we are!”

I love to ride, my mountain bike is rarely sitting idle. If you ride long enough you will be involved in some type of emergency. The younger and older riders seem to have the issues: the younger riders breaking their bodies, the older riders’ body parts breaking down. It results in the same need, immediate emergency help out in the middle of a wild park. And directing emergency responders through wilderness parks with the common map and signage systems is a crapshoot.

I created the trail junction project after a scary incident involving my brother. He’s fine, but the event made the inadequate system personal. The project involved a spiderweb of government agencies and public groups: Clark Regional Emergency Services Agency (CRESA), Clark County Parks Department, Washington Trail Alliance (WTA), and my two bicycling clans, the Northwest Trail Alliance (NWTA) and the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA).

The mix of groups, lack of existing relationships, and technical system limitations made the project complex. Understanding how the emergency technical systems worked at the dispatch and responder levels, then the needs of all the humans involved, dispatcher, responder, caller, injured, all fell into the normal bounds of a technically slanted HCD project.

There are the two problems we had in the PNW trail systems that I worked to solve: 1. How do you know where you are? 2. How do the responders get to you?

Callers’ fear

It’s not like you plan to call for help. You just call. You may recall seeing a sign not too far away. You head over there, and find the sign named Northridge Way. That’s great, but that trail is three miles long. How do you tell them where you are? GPS may be working, but in a lot of wilderness parks with steep terrain, the kind mountain bikers like, it doesn’t. You hope that you told them where you are well enough they can find you. If you have a spare person, they can ride out to a commonly known spot and lead the responders to where they are needed. If you don’t have a spare person, are new to the area, or are busted up alone … It’s a crapshoot.

Responders’ dilemma

After a call comes in, the dispatcher asks where the person is, and if GPS is working on the person’s cell they may get a location and from that an address for the park. Due to the park terrain sometimes the GPS signal is unavailable. Cell tower triangulation isn’t accurate enough to be much help.

In the emergency services computer systems, when an address is entered, the dispatcher and responder see the address, and an attached file specific to that location. Think of it as a tweet with a PDF attachment. That PDF is how responders can get additional details they may need, like a map or special instructions.

Imagine driving to a scene as a responder and looking into an old-growth, 400-acre park with a crisscross of trails. Where are they? They are on the Southridge Loop trail, but that is a 3-mile long loop, and where? What are the trails like? Is it a gravel road or a 6″ wide primitive trail? Is it flat or steep? Even if you do know exactly where you are, you ask yourself if it’s better to come in the front or side entrance?

Requirements

No training – It had to be simple enough to be understood the first time a trail user and responder looks at it.

Scale – It had to scale across a wide range of named parks that have a defined boundary. It should work in huge parks like Yosemite National Park (750,00 acres) and smaller ones like Whipple Creek Regional Park (400) acres.

Identify junctions – It had to identify and provide a unique identifier for any trail intersections. (These intersections are known as junctions.)

Note: This system would not be applied to linear trail systems. These are more akin to highways, and can be over a thousand miles long. They use mile markers, like highways do.

Solutions

The in-park user testing combined with discussions with emergency services and responders told us we needed a two-part system: 1. Signs in the park that told users what junction they were at, and 2. A map for responders to know where they are, and how best to get there.

Junction labeling

We gathered best practices from other areas of the country, testing the best numeric-based solution against what we created. And then we tested them …

Numeric

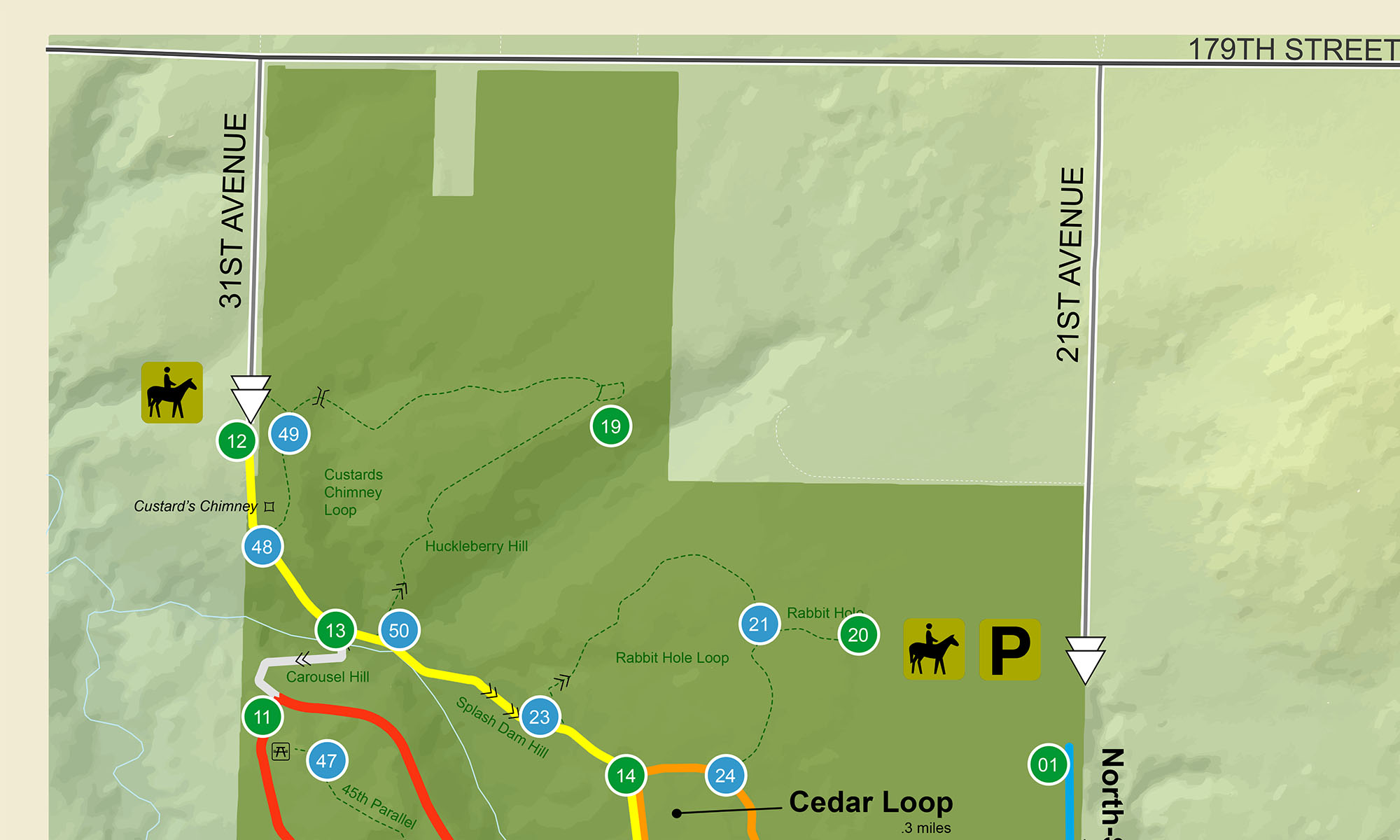

Numeric labels are simple, put a number on every junction. If you add a new junction, add a new number. It’s a simple concept, which also makes it the most commonly used method across the country. They aren’t in any particular order due to the nonlinear nature of wilderness trails and how they intersect. Users took up to 90 seconds to locate a junction. It became a game of Where’s Waldo. Result: FAIL

Grid

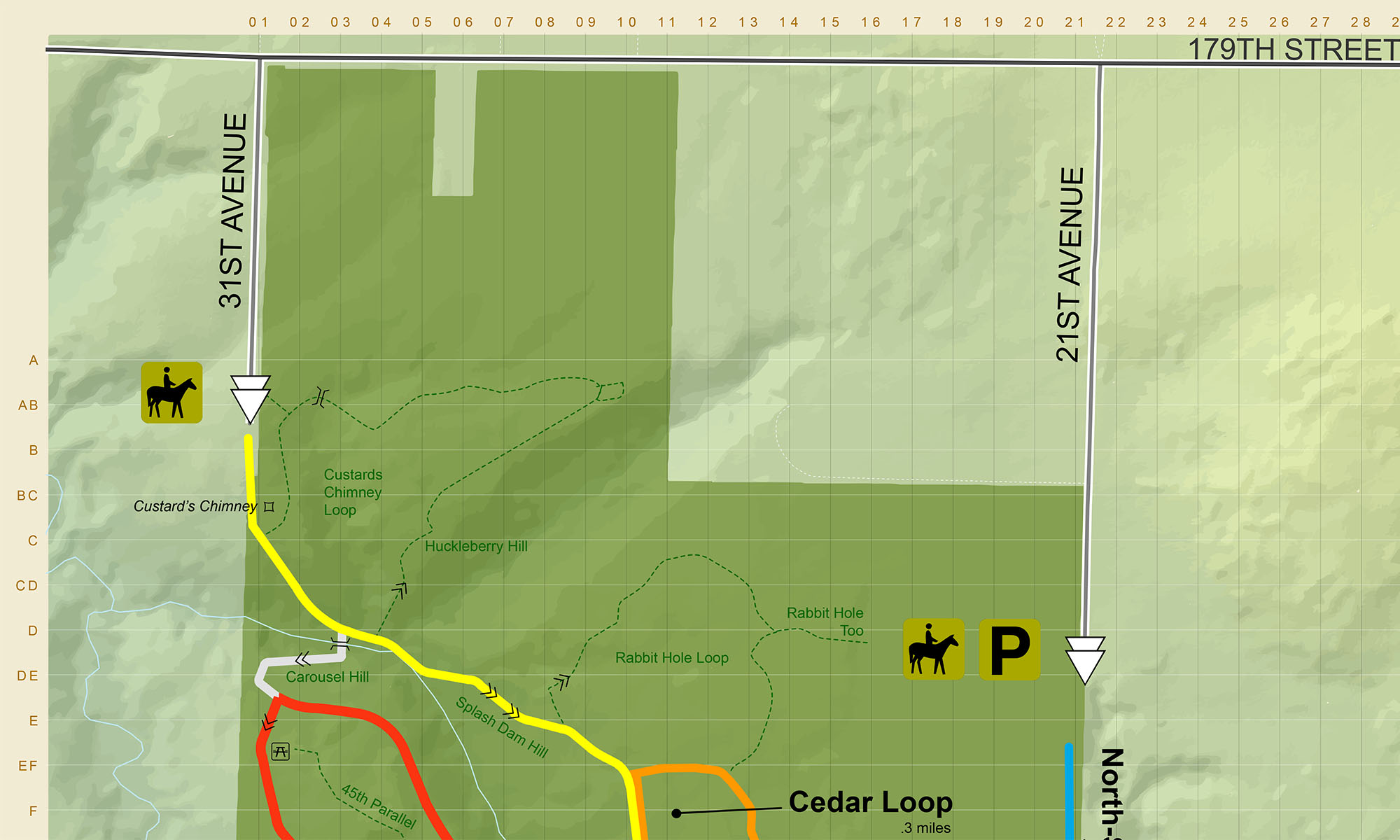

An X/Y axis grid is more complex to initially understand, but locating a junction is a simple task. Adding a new junction requires no change to the maps or existing park junction signage. An unforeseen benefit is that if a call comes in, the dispatcher can tell the responder exactly where the caller is using the grid, even if the caller didn’t know.

Users preferred this approach and the results showed why. The time needed to locate a junction is a very consistent, two seconds, with no drop in usability while viewed in a moving vehicle. The grid solution makes life easy on the dispatcher, paramedics, and park crews. Result: SUCCESS

Which entrance

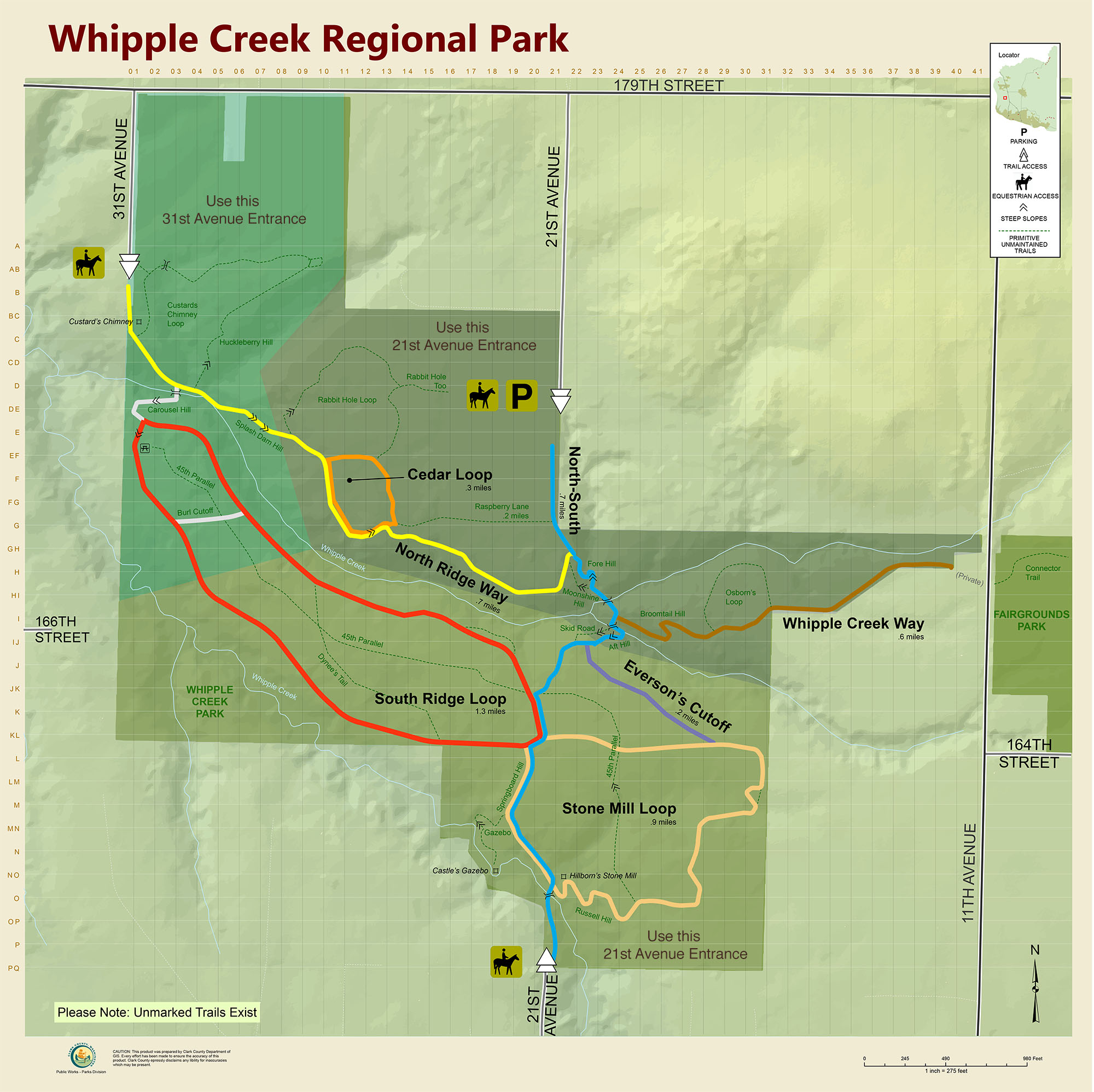

The address of a park normally corresponds to the main entrance. But the best way to reach someone may not be the main entrance. This responder specific map uses colored backgrounds to segregate areas to show which of the three entrances they should use for fastest access.

Signage in the park

Tests have shown people forget things when they’re stressed. To combat this short-term cognitive issue, the junction signs are placed at every junction telling the user to call 911, what park they’re in, and finally the junction identifier.

Sharing the knowledge

My junction signage and map learnings, and corresponding design system specifications will eventually be available through the IMBA’s website.

It’s worth the effort

It takes time and money to apply the system to each wilderness park, but now there is a system design available that works consistently. And unlike today’s park experience, it won’t cause a game of Where’s Waldo when a life is on the line.