NOTE: This is part one of the Whipple Creek Park project. Part two provides details on the locating and emergency help aspects of the project.

Four hundred acres of second growth forest. Thirty-five thousand annual visitors. Horses, bikes, joggers, and hikers. Twelve miles of trails with mud up to your ankles. One-half mile for residential neighborhoods. That is Whipple Creek Park in Ridgefield, Washington. A park in the heart of a county that grew up around it with trails that date back a century. It’s a mountain bikers dream – a park minutes from your house.

The first time I rode through the park I got lost for 90 minutes. As a system thinker and experience designer, I was excited. The forest was a new challenge to figure out.

I spent hours talking to people in the park. How long have they been using the park? What was their favorite? Where is that trail?

Can you see the trail here? We are standing right where it starts. There are crisscrossing primitive trails all over the park. With no signage or distinguishing features, no wonder new park users get lost. I spent the next few months learning the park inside and out. I also came to discover it’s easier to find trails in the snow.

The scare

This is my big brother John. The brother I always chased and looked up to. I took him to the park for a nice ride. Unfortunately, after a few minutes, he didn’t feel well, his heart was hurting and I had to lay him down on the trail. I had no way to tell the paramedics how to find us. And due to the geography, there was no GPS signal to track. The park maps were so out of date and just plain wrong that they were useless. If this had happened before I got to know the park inside and out, I would have had no way to get him help.

Others were at risk, and I had the skills to fix the in-park experience, trail confusion, emergency response, wayfinding, and signage systems.

Park users

The first step was figuring out who the park users were. The high-level personas were pretty straightforward: horse riders, hikers, joggers, mountain bikers, volunteers, emergency responders, and county maintenance workers. And their time in the park: first timers, casual, and experts.

Their feedback was summarized by these statements:

- Is this a trail?

- Where does this go?

- Where am I?

- Where is the historic relic?

- Let me out!

- If I get hurt, I’m @$#%^d!

- We need an escort to find anyone in there.

- I get a work order, and it takes me an hour to find it (a downed tree) in the park.

Through conversational interviews inside and outside the park, we came up with our project goals. Everything would be evaluated on how it supported these goals. They were:

- Simplify

- Know where they are

- Let them out

- Make the trails flow

- Direct outside help

Fixing the maps and finding the “secret” trails

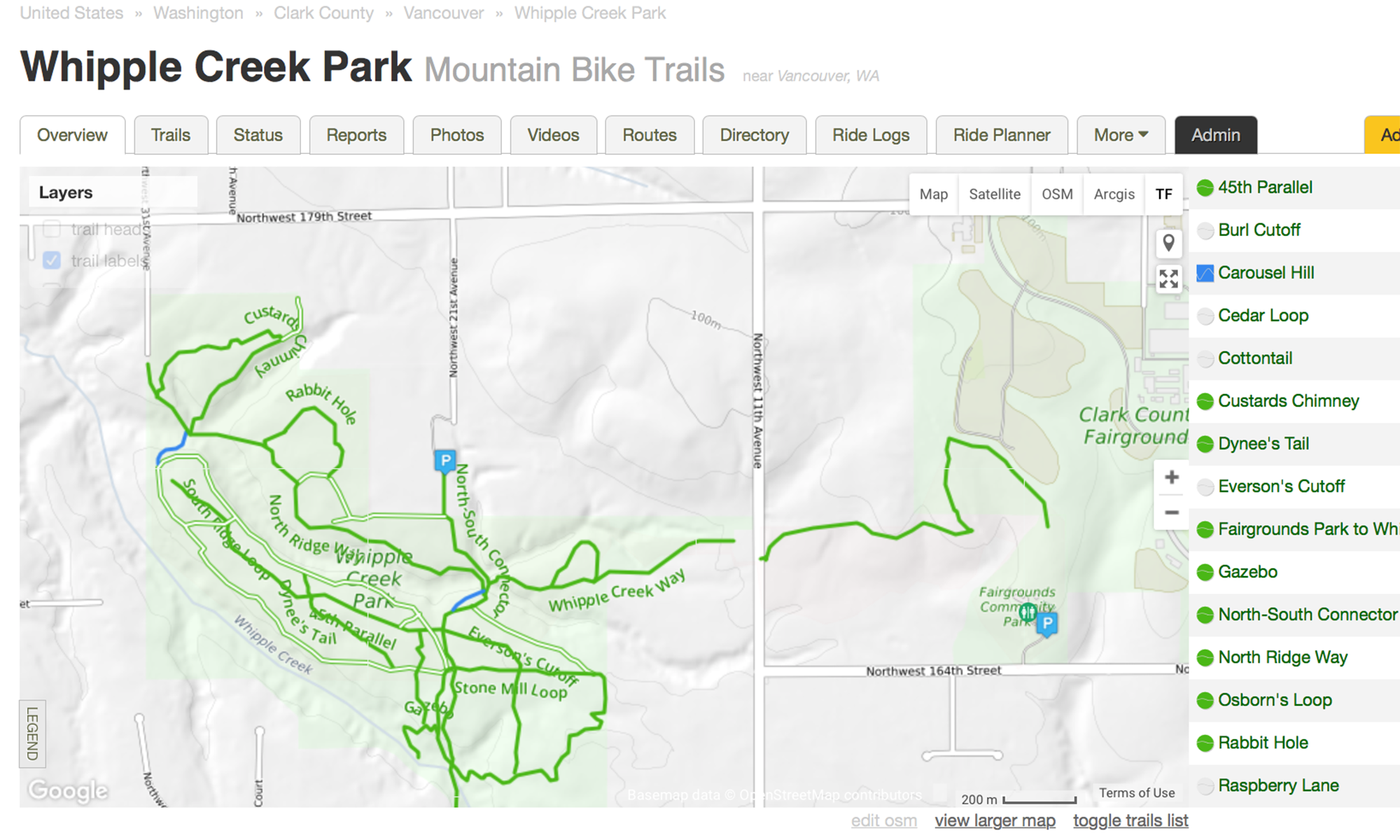

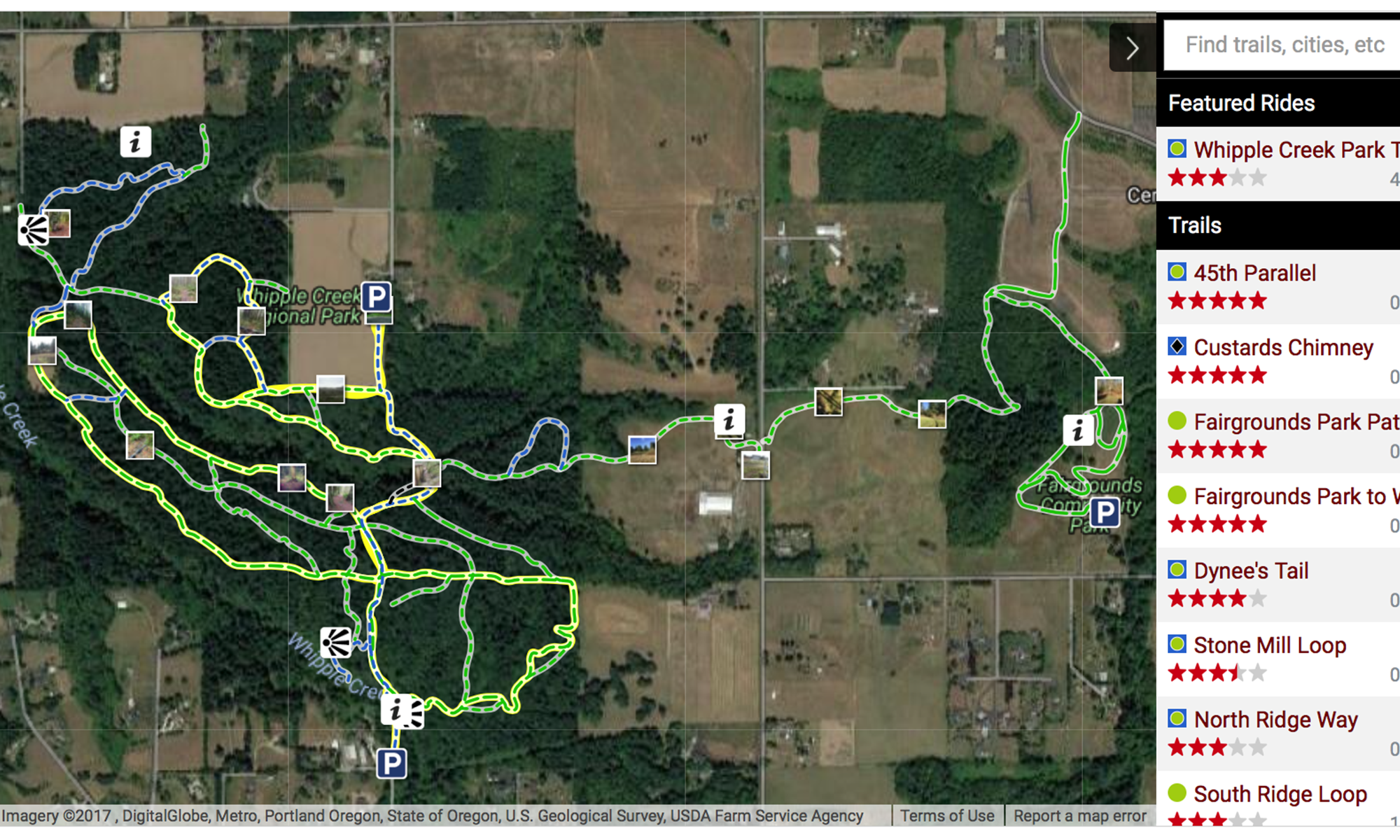

The first place to start was getting a lay of the land. The maps looked fine at first, but once you knew what was going on, it was obvious how useless they really were.

The county maps in the park were completely inaccurate. The maps were so bad in fact that people started writing on them with all sorts of corrections.

Expert park users had their own secret trails. The entrances to them were hidden and unmaintained. I came to learn that even the park experts lacked a complete view of the trails. I gathered bits of information and pieced together a general idea what existed. I started exploring, getting lost. All the while I recorded the rides.

Expert users who shared their secret trails with me were very worried that by sharing them, the county would know about them and try and close them. Getting them to trust me enough to share their secret trails was a delicate undertaking.

After a few months of mountain biking adventures, interviews, and a run in with some coyotes, I had a complete view of the trail system. It was a lot bigger than anyone knew! Twice the size.

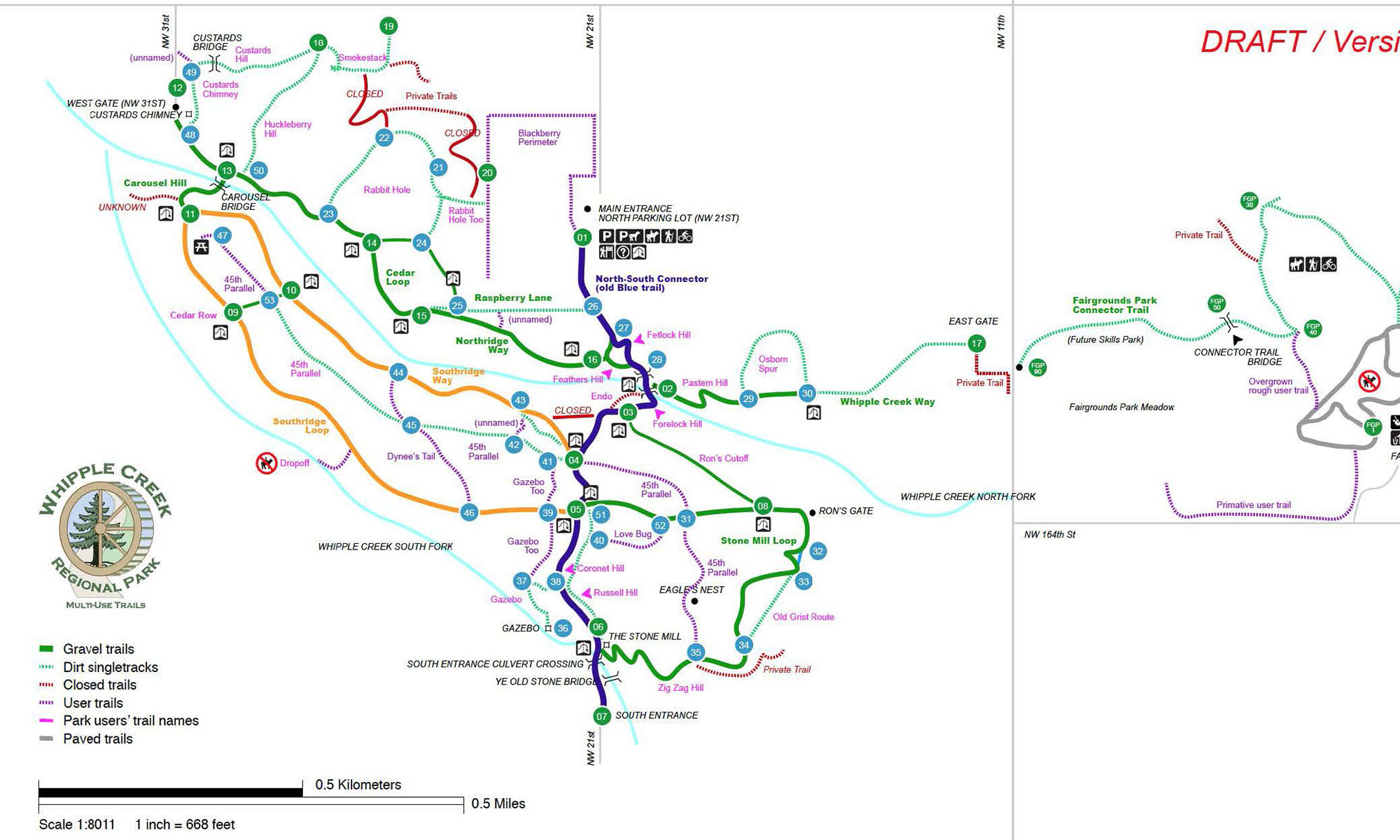

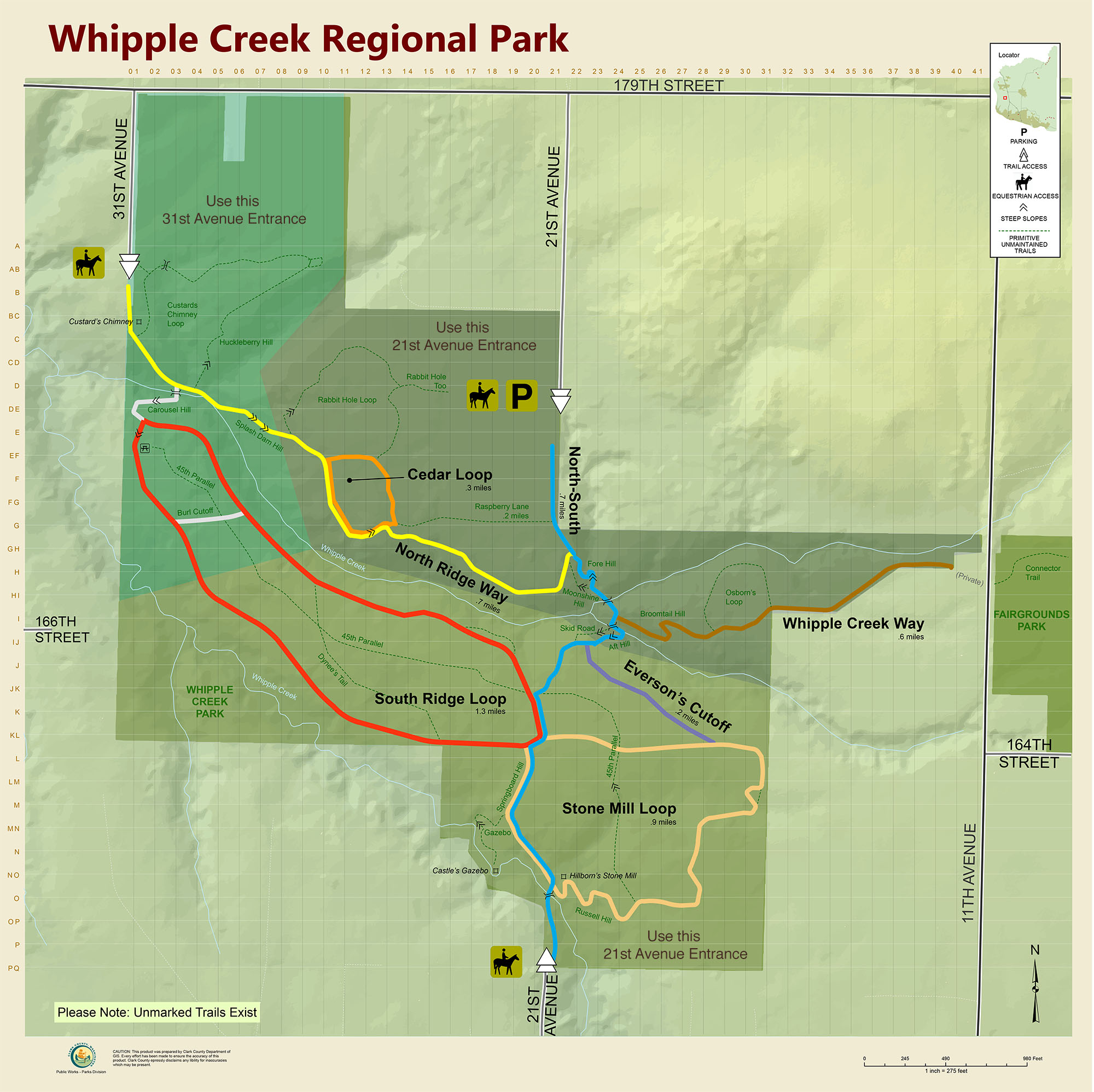

Even some of the main trails were mapped wrong. Main gravel trails (colored) were corrected, and all the newly captured primitive dirt trails (green) were added to the map. I added all the trails to the county’s map, giving them their first ever complete trail system map.

Using trail names to tell the park’s story

I used the new primitive trails and the park’s hills as an opportunity to tell the park’s story. Taking the time to ensure that each name meant something. So that each trail name reflects something or someone of historic significance. Some more heart warming than others …

Dynee’s Tail (Historic) Dynee was the pet of a young boy named Peter. Dynee spent countless hours in the park helping keep those working on the trails company. Chasing his tail among other things. Though Peter died at an early age, Dynee came to the park many times to keep the trails clear.

The proposed names went to the Clark County Park Advisory Board and several neighborhood associations for approval. In the end there were no changes required. It was a long process, though. The approvals took 9 months.

Inspiration from the highway system

In some cases, the trail name needed an additional description. For these, I borrowed from the US highway naming guidelines making them more intuitive.

- Loops – Circle back on themselves

- Spurs – Leave a trail and don’t return

- Ways – Take you to a destination

- Cutoffs – Are a shortcut

- Too – Are adjacent segments that aren’t long enough to justify their own trail name

Taking care of the signage

The signage in the park was a complete mess. A random mess of signs that people crafted, and hand-written sharpie additions.

The park signage fell into two categories: messaging and directional. Both needed help. The goal was pretty simple.

- Change the attitude of the messaging

- Reduce the quantity and complexity

- Guide users to the exit

- Direct help

Attitude and quantity

I inventoried the signage and went about consolidating and rewriting the signage. At the trailhead there were a random soup of 17 signs. Using what I learned developing the Winning with Words program, I was able to get that down to three. And I wrote them with an engaging tone inspired by the work of Cameron Stewart (North Vancouver, BC sign maker).

Directional signage

Designing the directional signage and updated maps was one of the most complicated and time-consuming aspects of the park project. It involved working with the Clark Regional Emergency Services Agency (CRESA) and Clark County Parks Department on how best to ensure that callers and emergency responders had what they needed to receive and provide help. It’s covered in detail here: Coordinates in the Wild

There were plenty of signs in the park. Wrong names, wrong directions, and sometimes they would go missing. You see, wood signs are pretty and a major target for thieves. They also can’t communicate the subtleties the directional signs needed.

Lean UX at its best … real-time iteration with brown sharpies, and white vinyl stickers

After the signage system was done I focused on park usability. Directions are tricky; how someone perceives space changes their interpretation. Over a month I took multiple users on a tour of the park and at each junction asked them what the signs were trying to communicate. These field user feedback sessions made sure the signs would send people where they wanted. It took three rounds of adjustments to get it to a near-perfect success rate.

After a county approval, the rapid prototype signs were replaced with permanent versions.

Making the trail routes intentional

The trail system grew organically; some of the trials were wildlife trails, others old logging roads. It was never planned to provide a good flow through the park and minimize congestion or collisions between horses and bikes.

Together with the county, Washington Trail Association (hikers), Executive Horse Council (horses), and my friends at the Northwest Trail Alliance (bikers), we worked on a proposal to provide a connected primitive trail system that minimized jumping onto the highly used gravel trails. It enabled primitive trail users an enjoyable flow through much of the park. This required closing some trails, rerouting others, and cutting completely new trails.

It took nine months to accomplish, but it was worth it. The end result is an intentional flow and significantly more enjoyable ride through the park.

Sharing the park – the new-fashioned way

For a park that had over 35,000 visits annually, there was very little online community engagement beyond a stale website and Facebook page. We changed that.

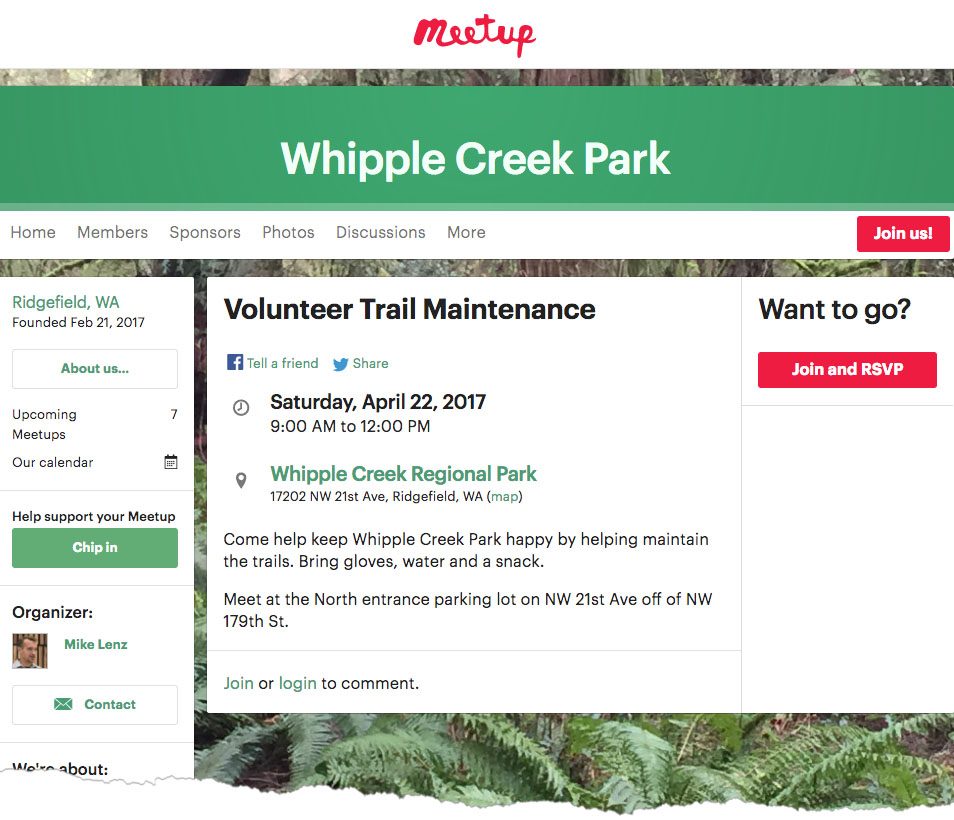

The Meetup volunteer trail maintenance group pulls in interested individuals and groups from the surrounding metro area.

The Meetup volunteer trail maintenance group pulls in interested individuals and groups from the surrounding metro area.

In addition to sharing pretty pictures, Instagram is used in conjunction with a trailhead sign to share the current park conditions.

In addition to sharing pretty pictures, Instagram is used in conjunction with a trailhead sign to share the current park conditions.

Eighteen months to make it intentional

The entire county has grown up around the park, and over 18 months, a few hundred hours, and lots of HCD passion it just intentionally did too.